Time Lapse: Reframing the photography of Pogus Caesar

By Derek Horton

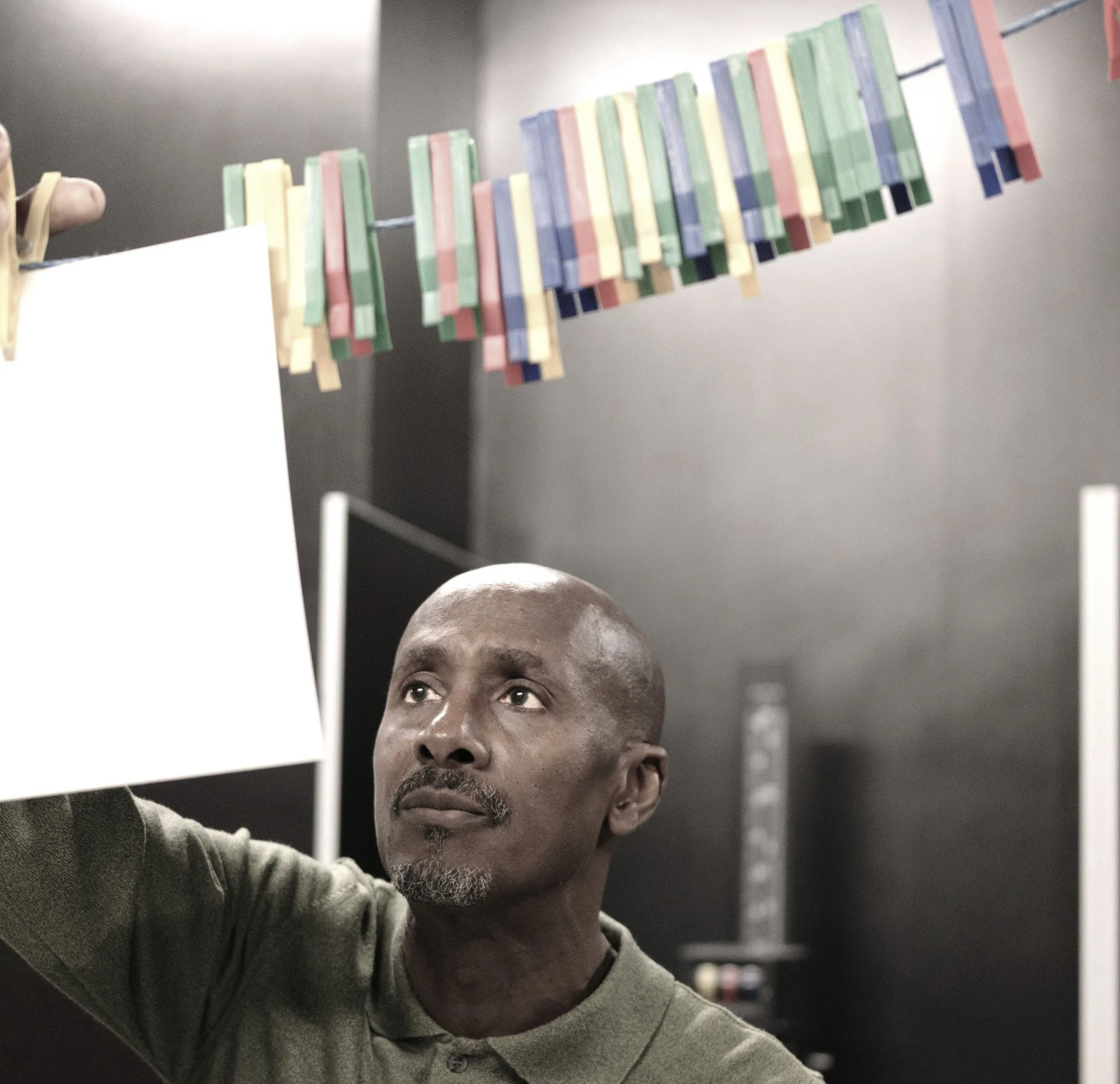

Pogus Caesar photographed in Birmingham by Christopher Waggott/DACS

Pogus Caesar’s work as a photographer spans continents and decades, features the famous and the unknown, capturing moments of joy as well as documenting trauma and violence. His work will be featured in the upcoming and highly anticipated exhibition at Tate Britain, LIFE BETWEEN ISLANDS CARIBBEAN — BRITISH ART 1950s — NOW.

What unites the many images across this diverse body of work is a strong commitment to portraying all his subjects with dignity and respect. The prolific and influential Afro-American photographer Gordon Parks, more than a half-century ago, called the camera his "weapon of choice" against racism, poverty and injustice. Caesar is part of that tradition of empowerment through Black self-representation.

During Black History Month in 2018, Caesar used his social media account to make daily posts of portrait photographs from his archive. Often criticised as a token gesture that continues to subordinate Black history rather than radically insist on its centrality to mainstream histories, Black History Month's own history is an interesting one. It was first proposed by the Black United Students organisation of Kent State University, Ohio, in February 1969, and the first wider celebration of it took place the following year, incidentally only weeks before the National Guard shot dead four unarmed Kent State students protesting the Vietnam war. February is still the designated month in the USA, although it is now celebrated in Europe in October, and was chosen in acknowledgement of a much earlier precursor. In 1926, the Black American historian Carter G. Woodman and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History had announced the second week of February to be 'Negro History Week', a date chosen by Woodman because it coincided with the birthday, in 1818, of the African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Black Skin, White Palm, Same Blood, London, UK 2008. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

Born into slavery, Douglass later became an extraordinarily important social reformer, statesman and writer, famed for his oratory. He is perhaps less well known for his considerable interest in photography, which was invented during his adult lifetime (the daguerreotype was introduced in 1839, just a year after he escaped from slavery). Douglass was the first person to understand that photography had potential as a democratic medium, capable of bringing about social change. In 1861, he gave a lecture titled Pictures and Progress, in which he developed one of the most historically significant theories of contemporary photography, identifying how photography could be a powerful force of positive self-representation in the fight to overcome racism. He embraced photography as a technological weapon to challenge caricatures, ubiquitous at the time, that portrayed his race with exaggerated features and reinforced white supremacy by representing Black people as simple-minded and subjugated. Douglass believed that the medium could produce what he called ‘a morally true image’ of the Black subject that asserted his equality and harmonised with his observation of himself and his freedom. He maintained that photography could highlight the essential humanity of its Black subjects and restore a dignity that centuries of oppression had denied them. In posing for scores of portraits throughout his lifetime, he used his own image to show what black freedom looked like. By the time of his death in 1895, Douglass was probably the most famous and recognised Black man in the world. In his many portrait photographs, dignified and fearless, always looking directly into the camera, he is no longer the runaway slave but the powerful face of freedom.

Tremble, Jamaica 2008. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

So since the 19th century, the photographic portrait has had the potential to allow Black people to represent themselves as they want to be seen, not how others pigeonhole or even dismiss them, and ideas that stem from Frederick Douglass have continually informed and motivated Black photographers ever since. The great Roy DeCarava said in a 1996 radio interview that when he started taking pictures in the 1940s, “there were no Black images of dignity, no images of beautiful Black people. There was this big hole. I tried to fill it.” This recognition that photography has a unique ability to dignify, to give importance to its subjects and celebrate their lives and their humanity remains central, more than a century after Douglass, to Pogus Caesar’s portraits. To decide to photograph someone or something is to tell the world that it matters and deserves attention to be paid to it. Caesar’s powerful images seek and hold our attention, focusing it on the varieties of Black experience they document and celebrate.

My House, New York, USA 1999. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

While bearing witness to confrontation and violence in photographs such as those of the Handsworth Riots, Caesar’s portraits of everyday life (the dinner ladies of Holyhead School in Handsworth who returned to public view in the Shakespeare’s Globe poster for The Merry Wives of Windsor, for example) are also celebratory, representing from a personal perspective the dualities of hostility and welcome in the African-Carribean experience of life in the UK. Although the overt racism of the 50s and 60s and the street violence of the 80s may be gone for now, the UK government’s recent policies towards the Windrush generation and the underlying racism and the return of the hard-right uncovered by the Brexit debate are just two examples of the pervasive attitudes of white supremacism that persist in Britain under the cover of contemporary liberal social values. Caesar’s pictures demonstrate a clarity of vision about both the positives and negatives of Black experience alongside a fundamental humanistic optimism in his mining of his personal life for inspiration and subject matter.

Dinner Ladies, Handsworth, Birmingham, UK 1984. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

Positioning Pogus Caesar’s extensive body of photographic work within the context of conventional genres of photography poses some intriguing dilemmas. Sometimes described as a documentary photographer or a photojournalist, his approach lacks the immediacy that this might suggest. Undoubtedly his photographs are important documents — of both momentous events and daily life, of people and places, especially his native Birmingham — but their meanings shift and become richer as a result of the distance between the photographic moment and its realisation and visibility. For example, his famous photographs of the Handsworth Riots in 1985 remained unseen for twenty years, not only by a wider audience but by Caesar himself, since the film remained undeveloped and the negatives unprinted until 2005.

Handsworth Riots, Birmingham, UK 1985.

The role of the photograph as ‘evidence’ is brought sharply into focus here. If the photographs had emerged immediately into the world, as they would have as reportage in the hands of a photo-journalist, they may well have been sequestered as evidence in a legal sense against alleged rioters, possibly even against the photographer himself. This may be one of many reasons Caesar withheld them from view, even his own. That they remained literally black, as unexposed film, for decades, gave them an increased significance as evidence of a different kind when they were finally shown. They are of their time but also, in their continuing relevance, have a kind of timelessness. The time lapse adds to their importance as historical documents of the justified uprising of a community against state power and oppression.

The 1985 riot photographs were given a new context in 2019 when aligned with poems by Benjamin Zephaniah on a series of large billboards that were displayed in multiple sites across Birmingham. Handsworth 1985 Revisited was the culmination of a collaborative project three years in the making, they formed a provocatively inspiring but sobering and timely reminder that the injustices of a grossly unequal society can all too easily be stretched to breaking point. The resurgence of the far-right in British politics, the prevalence of casual racism normalised by the Brexit debate, continuing institutional racism in many aspects of our society and an increase in violent racist attacks, all demonstrate clearly that the tensions, divisions and trauma that cities like Birmingham endured in the 1980s have not gone away, but are deepening in our present climate of poverty and austerity for the many and extreme wealth for the few. The billboards project, combining Caesar’s very personal documentation of social unrest with Zephaniah’s powerfully humane and rhythmic poems, engaged a whole new audience and reconnected the injustices of the past with those of the present. The wider audience that billboards make possible is important to Caesar and further recent projects brought images from the Black Lives Matter and Music Kinda Sweet series to the streets of London, Birmingham, Glasgow, Brighton, Edinburgh, Bristol and Cardiff.

Handsworth 1985 Revisited, Birmingham, UK 2019.

Caesar’s work has taken him around the world, including to Spain, India, Latin America, Sweden, South Africa, Albania, the USA and Jamaica. For better or worse, “wherever you go, there you are”, is what someone once said about travel, and this is true of Pogus Caesar’s photographs. Wherever in the world they are shot, they are reflective of his own life and his own experience of those places — the citizen of Birmingham is a citizen of the world, but for Caesar the reverse is always also true. Wherever his work takes him and wherever his images transport us as viewers, his home city of Birmingham runs through his work as a connecting thread, a centre of gravity that grounds him and his work. The political geographer, David Harvey, has argued that the only way to seize control of cities from rampant capitalism and to “build and sustain urban life” is to assert our “unalienated right to make a city more after our heart’s desire”. Perhaps I am influenced by my own attachment to Birmingham, but I see and feel that assertion in Caesar’s photographs, and they certainly have contributed to that sustaining of urban life in his commitment to his home city. Such a subjective response on my part is legitimate I think, because generally Caesar relies on viewers to make their own connections between himself and the artworks. Of necessity, the photographer is normally absent from the photographs they shoot, and, especially in documentary photography, it is a convention of viewing that we don’t imagine the photographer’s presence in the scene, or indeed anything else outside the frame. Somehow though, in Caesar’s work, one always feels his presence and its influence on what we are seeing. The very personal and specific can at once be all-encompassing and expansive.

Day Trip to the Black Country, Walsall, UK 1986. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

In a culture that expects specialisation he might be regarded as something of a dilettante, but arguably the diversity of his life experience contributes to a very particular capacity for reflecting life’s multiplicity in his work. One of Caesar’s strengths as an artist is that his photographic practice exists alongside an impressively diverse range of other activities. Their sheer variety — chef, pointillist painter (which is where his artistic adventure began), curator, TV newsreporter, film producer and more — informs the photography which has been a more or less constant and ongoing thread through his multiple occupations. At one level, Caesar’s approach is an existentially simple one: he lives his life in his community and he always carries a camera, and so has always kept a comprehensive record of that life and that community.

It is a very substantial record too, consisting now of an archival collection of more than 19,000 35mm negatives. The essential simplicity of this approach extends also to the technical aspects of his photography. In 1986 he exhibited his first photographic work, Instamatic Views of New York at the National Museum of Film and Photography in Bradford, it consisted, as the title indicates, of photographs taken with a very basic Minolta 110 Instamatic camera. Subsequently he upgraded to 35mm fixed lens Canon Sure Shot that has become the sole tool of his trade that he still uses today. Working with this very basic camera, and almost always with available light, producing rough, grainy images, he has no interest in the burgeoning high technology that impacts on most professional photography, but which is unnecessary for his very straightforward method, where the subject and the image are more important than the technical sophistication of their production. He is constantly shooting things that interest him, subjects he cares about, that matter at the time, and then holding on to them. Giving a new meaning to the term ‘time-lapse’ in photography, he often reconnects with the photographs ten or twenty years later, as if for the first time, with all the hindsight and new perspectives that such a delay brings.

Untitled, Spain, 2003. From the series Schwarz Flaneur.

Every photograph holds a date, a specific time and place, within its continued existence as not just an image but an object. Histories are carried within each frame of film; the history that has formed the person who is the subject of the photograph, the history that has led to them and the photographer being in the same place at the same time. When the negative is printed and viewed, these histories combine with the history of the time elapsed between that moment and our viewing of the photograph, and our own history that informs the way we see and ‘read’ the image. The question of when a work of art ‘happens’ is often implicit in Caesar’s images: is it the moment of its production — for a photograph the moment captured in the brief instant the shutter is opened — or the time it meets its audience, when it is published or displayed? The conceptual gap between the artist’s intention and the viewer’s interpretation is mirrored by a temporal gap between the event recorded in the photograph and the time it is seen — seen again as an image by the photographer as viewer of his own work, or seen for the first time by the rest of its audience whenever and however they encounter it.

Pivot-A Stronger Pull, London, UK 1989. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

Just as Caesar does not fit neatly into the documentary category of photo-journalism, neither is he directly part of the tradition of street photographers such as Lee Friedlander or Gary Winogrand. They were self-consciously making photographs as artworks and their working method in relation to their subjects was essentially one of opportunistic voyeurism. Caesar is much more involved in the photographs he takes, connected to his subjects, and a part of the communities with whom he works. Some of his photographs show mundane aspects of people’s everyday life on the street, in the home or at work, while others are of widely recognisable subjects, ‘stars’, whose images are part of a common cultural memory. To some degree though, they all bear witness to racial, class and geographical difference, whether they show anonymous figures or the more commonly recognised. That is to say, for example, an image of Lenny Henry ‘means’ something different to an African-Caribbean viewer from the West Midlands as compared to a middle class white viewer who has only seen him on television. Caesar’s photographs reflect people at the intersections of different identities and genres of cultural expression, showing wide varieties of authentic Black experience that are validated by his honest, empowering, and positive representations. While media images frequently commodify Black trauma and tragedy, these photographs, whether of children playing on the street, school cooks and dinner ladies in Handsworth, or portraits of musicians, in the series Muzik Kinda Sweet for example, are intimate and purposeful images of the dynamic, resourceful and creative aspects of Black culture that more often celebrate Black joy and wellness.

Stevie Wonder, Birmingham, UK 1989. From the series Muzik Kinda Sweet

The powerful series, US of A, looks at religion, sex, identity and race, bringing an alternative narrative to the American experience from a Black British perspective. Cooking Ice, from this series depicts the failings of former President Nixon’s “war on drugs” in which in 1971 he increased the power and funding of America’s federal drug control agencies. Over a period of time this policy increasingly resulted in a widespread public perception that predominantly associated African Americans with the consumption of hard drugs. Ice, commonly known as crystal meth, is one of the most dangerous and highly addictive drugs of recent years, created by mixing chemicals in a synthetic process known as cooking. It generates an initial feeling of euphoria but its psychological effects can develop into paranoia, obsessive behaviour and delusions of power. The outstretched hands in Cooking Ice symbolise the steel grip that drugs have on American society, whilst the stark background and distorted halo allude to the targeting of Black communities by the US administration. Decades later and billions of dollars spent, the war on drugs is still being fought with no end in sight. This artwork is an example of how the whole US of A series, working more experimentally with the photographic image and often incorporating text, documents in a multi-layered way the consequences of white supremacism in action.

Cooking Ice, 2015. From the series US of A

The series Represent features portraits, from Benjamin Zephaniah to Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Jay Z to Desmond Tutu, from Jesse Jackson to Paul Robeson Jr, almost all taken in Birmingham. The National Portrait Gallery has recently acquired eight of Caesar’s portrait photographs, made between 1983 and 1992; an acquisition that gives important national and institutional recognition to his significance as a contributor, from a Black British perspective, to the visual recording of recent Black history. The eight photographs are a striking and varied selection. The artist Sonia Boyce is portrayed simply and candidly in a study of thoughtful contemplation, whilst a youthful John Akomfrah, the filmmaker, beams a life-affirming smile at the camera, riding a bike outside Birmingham Town Hall. Artist Gavin Jantjes and poet Benjamin Zephaniah share a similar pose, head in hands, in two otherwise very different photographs. Looking directly into Caesar’s lens is the legendary photographer Vanley Burke, there is both warmth and sadness in the piercing eyes of the artist Donald Rodney, who died tragically young. The actor, comedian, writer and broadcaster Lenny Henry looks confidently outward at the world through mirrored sunglasses, whilst musician and record producer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry peers enigmatically over his shades, posing very deliberately in his characteristically eccentric fashion.

Donald Rodney, Birmingham, UK 1992.

Caesar’s vast archive of images, 19,000 and growing, is an important reflection of what Black history is and has been. However long it is since they were taken, whatever the time lapse between shooting and viewing, these images will remain an important historical record both of and from a Black British perspective. One of the best descriptions of Caesar’s role, I think, can be found in the title of another of his series of work, Schwarz Flaneur. Reflecting the figure of the flâneur as described by Walter Benjamin as a wandering urban spectator, an investigator of the culture of the city and its manifestations of capitalism’s alienation, Caesar might indeed be seen as a ‘Black flâneur’. His unassuming approach enables him to capture unguarded moments with a photographic gaze that is analytical but also caring and intimate. Their style and working method differ, but Caesar can be seen alongside photographers like Gordon Parks or Dawoud Bey as he explores the inherent beauty in being ‘unapologetically Black’, and presents us repeatedly with what, thinking about Black photography as long ago as 1861, Frederick Douglass called, ‘the morally true image’.

Protein III, Dudley, UK 1990. From the series Schwarz Flaneur

In his short story, Sonny’s Blues, James Baldwin suggests that to truly understand an artist, one must fully engage with that person’s oeuvre. At the end of the story, the narrator finally goes to a jazz club to listen to his brother play. “What is evoked in [the musician], then, is of another order, more terrible because it has no words, and triumphant, too, for that same reason. And his triumph, when he triumphs, is ours”, he tells us. “He could help us to be free if we would listen.” Engaging with Caesar’s oeuvre, with the multiple photographic series he has made throughout his adult life, can help us to envisage freedom through their focus on and amplification of histories that are often systemically marginalized. There is an intensity to his images that reflects the emotional and intellectual commitment involved — a single-minded dedication that provides a fierce, bright illumination of Black British collective memory, personal identity and what it means to be ‘home’ and to ‘belong’. These words of the late Maya Angelou quietly resonates with Caesar. “A bird doesn’t sing because it has an answer, it sings because it has a song.”

Text © Derek Horton 2021 https://independent.academia.edu/DerekHorton/CurriculumVitae

Images © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2021

Parents Today/Handsworth 1985 Revisited © Benjamin Zephaniah/Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2021

Life Between Islands Caribbean-British Art 50s — Now, Tate Britain, London

01 December 2021–03 April 2022